What is a bad breeder?

If you were to ask the average person on the street, they’d probably have a clear image in their mind.

They’ll picture dogs in dirty cages, queens with multiple litters and puppies separated from their mothers far too soon. The person that profits off of the suffering of their animals—that is a bad breeder, right?

Overbreeding, puppy farming and lack of registration remain an issue, with an estimated 79% of puppies bought in the EU coming from non-legitimate sources. We can all agree that puppy farming is barbaric and should be combated with the full force of the law.

What’s more up for debate is this: what is “good” breeding?

When I set out to investigate the state of breeding in Europe, the ethics of breeding and if tech could help, I thought my focus would be on these puppy mills. But through my exploration and conversations with breeders, breeding associations and vets, I understood that “ethical breeding” is far more nuanced than it may first appear.

So nuanced, in fact, it leads to many breeders being painted with the same tainted brush—whether they deserve it or not—and an industry fragmented on what breeding should be.

Should all breeders genetically test their dogs for hereditary diseases?

Should all breeders abide by a strict standardised process?

Should all breeders be using the latest pet tech to ensure the health and prosperity of their litters, bitches and studs?

And—crucially—are you a “bad” breeder if you don’t?

This deep dive took unexpected turns into the world of the average breeder, the regulations they adhere to, the tools they use and the tech they’re crying out for. Here’s what I learned.

The problem

The statistic that 79% of puppies bought in the EU come from non-legitimate sources probably shocked you.

But let’s take a closer look.

The EU is home to over 72 million dogs and over 83 million cats. And yet, the demand for dogs in particular has risen dramatically in the last five years. According to a 2024 report by the global animal welfare organisation, FOUR PAWS, 5.99 million puppies are needed to meet the demand in Europe each year. If we include the UK, Switzerland, Turkey, Norway and Russia in our calculations, that demand rises to 8.77 million.

This report showed that only 21% of the demand for dogs comes from known (read: registered) sources.

However, those “unknown” sources could be:

- Puppy farms

- One-time, and now inactive, breeders

- Breeders who do not require registration

This is a key limitation of the data, which the authors acknowledge.

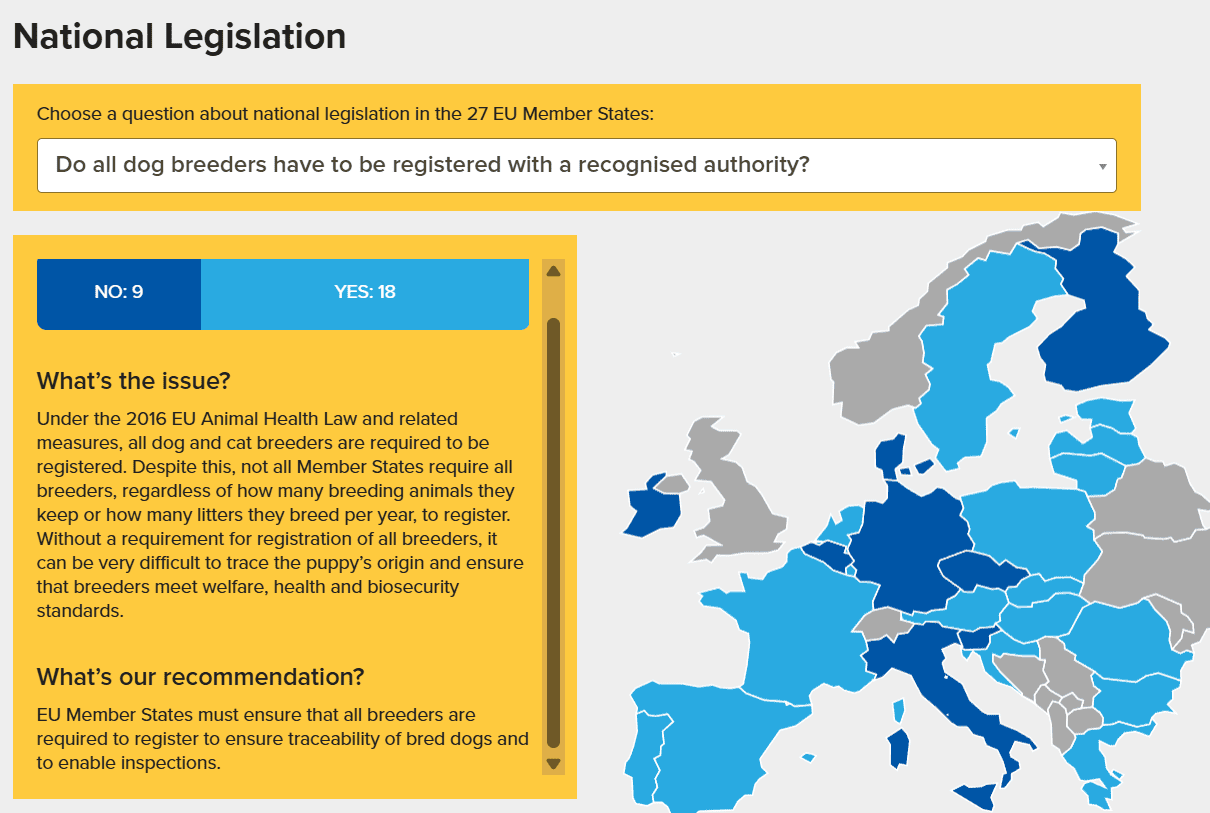

So, we have the first problem: the rules for breeder registration differ widely across Europe.

Registration

In Belgium, Denmark, the Czech Republic and the UK, a breeder can breed up to three litters per year without registering. Italian regulations only require registration after five litters, and in Ireland, you can keep up to six breeding bitches without registration. Part of the challenge here is that many small-scale hobbyists may not label themselves as “professionals” at all, particularly if they only do it once.

Standard Poodle breeder, Martina Ginz, pushed back at my use of the word “industry” when describing breeders. “We do not have a breeding industry in Germany. In most cases, breeders have one or two female dogs.”

Conversely, in France, Croatia, Estonia, Greece, Germany, Portugal, Spain, Sweden and Austria, all breeders (even “hobbyists”) with one litter must be registered.

Cockapoo and Cavalier King Charles Spaniel breeder Felicity Thorne said, “I think everyone who breeds should be considered a breeder. The rules are too complicated. Either you’re a breeder or you’re not.”

Of course, some breeders brazenly flout the regulations regardless.

In that case, a second problem is presented: traceability.

Traceability

The European Commission estimates that there are 32,000 registered breeders across the EU; however, it recognises the limitations of tracing puppies to legitimate breeders.

In their 2024 evidence report, which supports the legislative proposal on the welfare of dogs and cats and their traceability, they wrote, “Although identification (by way of microchipping, or tattoo if applied before 2011) and a European Pet Passport are needed for a dog or a cat to travel across Member States’ borders, based on the Animal Health Law 85 and the Pet Regulation (EU) No 576/2013, there is no obligation to register the animal in an EU-wide database. The system relies therefore solely on the information in the Pet Passport, which has been proven in practice to be easily falsified.”

Not only are Pet Passports easily falsified, but you also don’t need one until your pet crosses a border. So traceability within each country is highly dependent on the local laws.

A legal mandate to microchip dogs, cats and ferrets, passed in 2022, has seen great success in Portugal, with over 1.7 million pets registered by 2023. The Portuguese microchipping system is quite comprehensive, with a record of the owner’s details, the animal’s vaccinations and their registered veterinarian. That goes to show that regulatory changes can make a huge difference in public perception.

But if some breeders aren’t required to register, how can you confidently determine that even microchipped puppies are coming from good homes? Unethical breeders can easily disguise their sales as private instead of commercial.

Regulations

The third issue is the huge variability among breeding regulations themselves.

In some countries, breeding regulations are quite lean. For example, in Italy there are no national laws against breeding dogs with genetic conditions and no national database of registered breeders (only regional).

Other countries are quite strict; Austria has made huge strides to tighten their breeding regulations under the revised Animal Welfare Act, passed in 2024, which will take effect from 2026 onwards. It explicitly bans breeding dogs with genetic disorders, so breeders are now required to show documentation to prove that they’ve completed the mandated tests.

However, it’s worth noting that only 17% of the breeders and vets I surveyed for this article think that the breeding regulations in their country are sufficient, and 83% feel they could be doing more.

This is why many breeders choose to register with the Fédération Cynologique Internationale (FCI) and/or a breeding association within their country that have their own regulations on top of the national ones.

Breeder of Siberian Huskies and Danish Kennel Club (DKK) member, Jana Wolff, said, “I know that there are definitely good dogs without an official FCI pedigree, but I like the support and quality criteria that come with DKK breeding. For my part, I see the DKK requirements as a minimum requirement and have added my own standards to them.”

Tightened regulations accompanied with widespread educational efforts, in a bid to teach the public about buying from ethical breeders, seem to be the prevalent solutions put forth by industry experts and activists, despite the obvious implementation challenges.

But it was at this point that my research became more complex.

If registration is better enforced, and regulations are tightened, how does this impact the average breeder? And which regulations should be tightened?

Should all breeders be forced to be FCI accredited?

What should the cap on litters be? And should DNA testing be mandatory?

It was time to talk to the breeders themselves to learn more.

The good ones

Gathering research for this article involved interviewing 12 breeders from different countries and backgrounds.

Some breeders had extremely small-scale operations, only producing one litter every 2 to 3 years. Others had greater ambitions, with five breeding bitches. None of the breeders I spoke to had more than five breeding bitches or five litters per year.

The selection process differed depending on the breed and philosophy of the breeder.

Verena Piller of Canimagic Border Collies, a Germany-based breeder of Border Collies, said, “After health clearances, I wait around 2.5 years to evaluate character. At this age, they have passed their first tests and shown in many situations that they have the nerves and work ethics I expect from a Border Collie. It’s an important part of my personal breeding goal, to keep Border Collies working dogs with sheep sense.”

Martina Ginz, breeder of Standard Poodles, mentioned how show dogs were not important in her selection process. She told me, “Participation in shows and winning titles is not required for using poodles in breeding. That’s not important to me either, because as a breeder I need to be capable of judging whether a dog has the traits I’m looking for.”

Though selection processes varied widely, 100% of the breeders surveyed ran genetic tests on their dogs before considering them for breeding.

One breeder I spoke to, Anna Bergmann of Nordic Lassies, has waited, researched and planned for over ten years to ensure she breeds the healthiest puppies she can. She said, “In 2013 and 2015, I planned to start breeding dogs. Unfortunately, the queens I had at that time did not meet my high standards for breeding suitability. As I place health as my absolute top priority, I decided not to breed them and to try again some years later. That time has come now, and I am very excited for what lies ahead.”

The role of breeding clubs

As many of the breeders interviewed designed their breeding process through independent research, I wondered where breeding associations (kennel clubs) came into it.

Often breeders, and people in the public, see local kennel clubs or FCI-registered breeders and dogs as a seal of quality.

Some of the breeders I spoke to, like Ursula Arnold, breeder of African Azawakhs in Germany, are breed wardens of their respective clubs.

A breed warden is an official, responsible for overseeing the ethical and regulatory aspects of dog breeding, particularly within specific breed clubs or regional organizations.

Many breeding associations mandate genetic testing as part of their practice to become a member.

Arnold said, “The DWZRV successfully mandates genetic testing before breeding for certain breeds (Barzoi, Sloughi, Magyar Agar and others), as well as heart ultrasounds (Irish Wolfhound, Saluki, Afghan Hound), but this is not truly sufficient. Inherited health problems keep appearing, which are often downplayed or completely swept under the rug—frequently out of fear of being stigmatised by a mob on social media.”

Breeding/kennel clubs also provide educational materials to promote ethical breeding among their membership.

Elke Phillipy of Heart & Brain Australian Shepherds based in Germany, said, “The VDH (German Kennel Club) offers tons of good seminars for new (and old) breeders; luckily, since the pandemic, most of them are online. You can learn a lot about breeding, diseases, genetics and thus also what is already testable.”

But even breeding clubs struggle to reach a consensus on what the breed standard should be. Ellen Waßmann, President of the St. Bernhard Club in Germany, said, “There is a World Union of St. Bernhard Clubs (WUSB) with 23 member countries, and the St. Bernhard Club is one of them. Since we have repeatedly observed differing views among judges at WUSB shows regarding health-related aspects, the WUSB developed a guideline for judges.”

Only one of the breeders I spoke to was not a member of any breeding club; UK-based Cockapoo and Cavelier King Charles Spaniel breeder, Felicity Thorne, said, “ Providing the parents were health tested, I didn't see the point of paying extra for a KC registered when I was going to breed Crossbreeds.”

The vet perspective

In order to breed healthy dogs, cats, horses or anything else, it’s clear that you need a good understanding of animal health. Veterinarians are instrumental to ethical breeding, and yet many of the breeders I spoke to found that some vets weren’t so friendly to their cause.

There is a lot of contention in particular about “cruel breeds” or “extreme breeding”, which is when breeders select traits that are harmful to the dog. A controversial example of this is brachycephalic breeds like Pugs, French bulldogs, Boxers and Shih Tzus.

Licensed vet and Saint Bernhard breeder, Melanie Reimer, said, “Animals often don't show their pain or people don't recognise the signs of pain or suffering in animals. A French bulldog always works cheerfully and in a good mood but suffers from respiratory distress and nobody notices.”

Germany-based veterinarian, Sandra Götzfried, agreed. “The biggest issue is the conscious breeding with unsound dogs or the breeding of defects. It's often all about the money and not about the puppies' well-being or the future owners. Specific breeds that are overrepresented in my practice are French Bulldogs, old English/Continental Bulldogs and Labrador Retrievers with orthopaedic problems (hip or elbow dysplasia, ruptured cruciate ligaments, spondylosis, herniated discs, etc). I would welcome a more strict regulation for the Brachycephalic breeds or even a ban for these breeds.”

Both vets mentioned how they do their best to educate and support the breeders they work with.

However, it’s worth noting that veterinarians are more stretched than ever. The Health for Animals 2022 Global Pet Care Report showed that half of the veterinary practices worldwide reported an increase in caseload. So educating breeders on how to better care for their animals is one of many things your average vet is juggling.

How tech can help

Given that Unleashed by Purina’s primary goal is to champion pet tech innovation in Europe, LATAM, Asia and Africa, I turned my attention to how tech is already supporting ethical breeding practices and what more could be done.

How breeding tech is already helping

The adoption of tech tools ran the gamut from pen and paper purists to app lovers.

The most widely used vet tech solution among the breeders I interviewed was genetic testing.

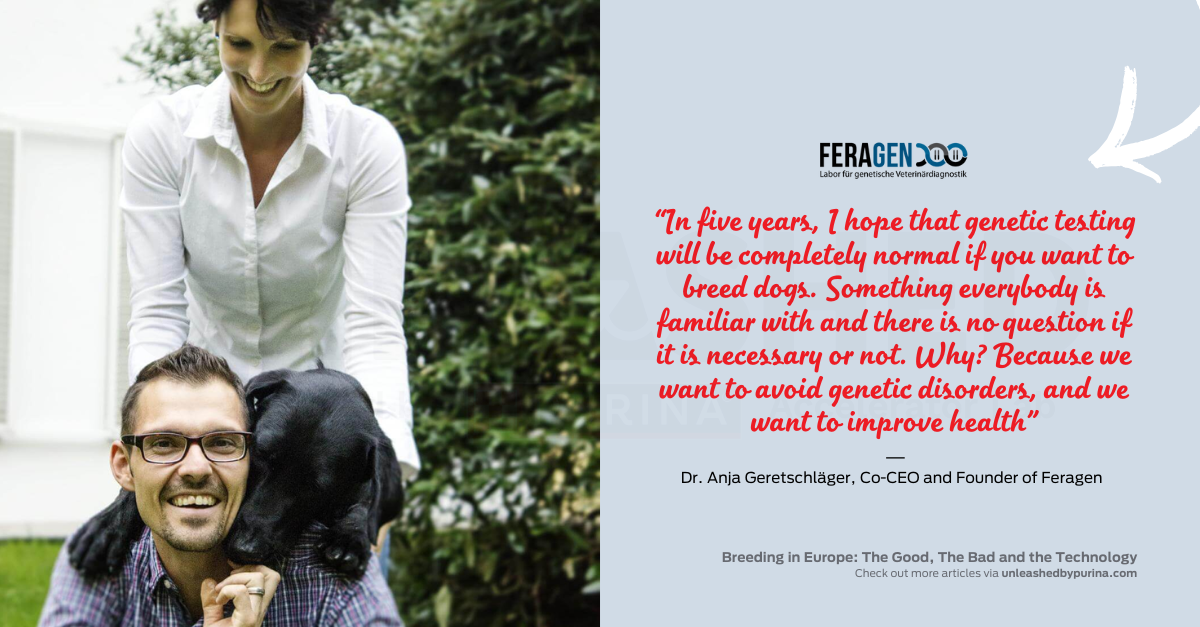

Pet biotech startups named in the breeder’s processes were Embark, Pet Genetics Lab, Laboklin and Unleashed by Purina alumni, FERAGEN.

This is not surprising as FERAGEN were instrumental in sourcing voices for this article, so I expected many breeders would’ve used their services. However, even breeders who had never heard of FERAGEN were staunch supporters of DNA testing.

“In five years, I hope that genetic testing will be completely normal if you want to breed dogs. Something everybody is familiar with and there is no question if it is necessary or not. Why? Because we want to avoid genetic disorders, and we want to improve health”, said Dr. Anja Geretschläger, Co-CEO and Founder of FERAGEN.

National kennel clubs in Europe are broadly on the side of genetic testing too. The UK Kennel Club even launched their own DNA testing programme in 2022, creating breed-specific packages at reasonable prices for their members.

The opinions of breed-specific clubs vary more widely depending on the attitudes of the board members.

Then there are health monitoring and tracking apps. Only 20% of the breeders I spoke to used any kind of software to track heat cycles, vaccination cycles, weaning timelines and so on. Tracking app, Puppy Center and breeding management software, Breedera, were mentioned.

I asked Unleashed by Purina Alum, Mike White, CEO and Founder of Breedera, for his take on tech adoption in the breeding space. He said, “Responsible breeding is something that people train their own lives to do. It comes with experience. That experience is now being passed down to the tech-ready generation. Things are changing.”

What breeders are looking for from their tech

When I asked the breeders what they felt would be helpful to support their work, simplification was the theme.

German Shepherd breeder, Anke Scholl of Wolfcubs, said, “A database where you can easily find everything you are looking for, so you don’t need to go to umpteen different websites and search for everything would be great. A test that contains everything you want to test would also be innovative. Either by making a selection yourself, or a combined test that simply contains everything that is currently testable.”

Though labs like FERAGEN, Embark and Pet Genetics Lab provide excellent services, right now breeders need to go to multiple apps to get a full spectrum genetic screen for each dog.

Danish breeder of Siberian Huskies, Jana Wolff of Carpet Rockets, said, “I would love to have an ‘all-in-one’ tool: A database with all the dogs, including all results from shows, trials and health tests. Helpful tools like a heat calendar, test matings and organisation software for the litters and buyers would be great too.”

Then, there will always be breeders who find tech too confusing or simply unnecessary to their processes.

For example, Standard Poodle breeder, Martina Ginz, said, “I don't believe that health monitoring apps for dogs are absolutely necessary or useful. The vast majority of dogs are healthy. The cost of pet ownership in Germany is already very high; in particular, veterinary costs have risen sharply. In light of the current political and economic situation, I doubt there is broad public interest in such apps.”

How tech help could fight unethical breeding practices

Though solutions like EU-wide legislation and databases are often mentioned by European Commission reports and animal rights activists, very few outline technological advancement in their proposals for change.

But, to my mind, there are several use cases where pet tech could be instrumental in supporting good breeding and how it could help with weeding out the bad.

For example, identification technology such as Unleashed by Purina alumni PetNow or NoseID could be used in registration and tracing efforts. However, the onus would still be on the breeder. And given the uphill battle it has been to get people to microchip their animals, implementing apps here could also face slow adoption at best and pushback at worst.

When I asked Sandra Götzfried, a licensed veterinarian based in Germany, about the use of health monitoring apps and genetic testing, she said, “These tools can increase the probability of breeding healthy and immune competent puppies. I think they should be mandatory, and the breeders should need to justify their decision if their breeding plan contradicts the test results.”

However, this approach could alienate some breeders who struggle with tech. UK-based Cockapoo and Cavelier King Charles Spaniel breeder, Felicity Thorne, said, “I’m not great with technology. It can get a bit complicated, though I do use Breedera. I find it easy to use, and if you've got any problems, someone answers you back straight away.”

Where do we go from here?

With so many dissenting opinions from just the small handful surveyed for this article, you can see why it’s so complex to come to any sort of consensus on the topic. The European Commission has highlighted the “uneven playing field” in every report they’ve ever done on the dog and cat trade in the continent since 2020.

But there were a few salient takeaways from the conversations mentioned in this article.

Legislation is the first pillar

The first point is that breeding regulations and, crucially, enforcement of said breeding regulations are far from where they need to be. But even regulations that are well-intentioned may miss the mark for certain breeds.

Elke Philippy of Heart & Brain Australian Shepherds said, “For two years we really had something going on in Germany (and a few other surrounding countries) regarding the strengthening of our animal protection law; particularly regarding ‘cruel breeds’/eugenics. There are a couple of breeds that aren’t worth being called ‘dog’ anymore—they have so many breathing, skin, eye and mobility issues. But the collateral damage for other (still healthy) breeds is huge—well-intentioned regulation isn’t always well-done. So in my opinion, the lawgiver has to be given proper advice from veterinarians, as well as from experienced breeders, to find a practicable solution.”

The fact that there is no EU-wide legislation for the protection of animals and that breeding regulations differ so widely across countries is partly why breeding practices are so divided.

There’s opportunity in breeding-tech

Secondly, though the adoption of tech wavers within the breeding community, there is a demand for simplified solutions that can support the health and care of their dogs and litters.

Genetic testing startups have seen good adoption rates on a global scale so far, and there’s a growing number of tech-loving breeders in the market.

Startups can also look at collaborating with government bodies to create innovative solutions to tackle traceability.

Reform comes from understanding

Lastly, and perhaps most challenging, humanising ethical breeders is crucial to revolutionising the breeding industry at large.

I ended every interview with this question: what’s the one thing you wish people knew about the realities of being a breeder?

The response of Kristina Schöller, a Sibreian Husky breeder, made me view this topic in a wholly different light. She said, “I wish people knew that breeders are also good people. That the health and the wealth of the dog and the owners are our main focus, and that we are caring about the dogs we breed.”

Mike White, CEO and Founder of breeding management software company, Breedera, echoed those sentiments, “It's a slight exaggeration, but everybody loves dog breeds, but everybody hates breeders. But if there were no breeders in the world, every dog would be a mixed breed. Breeders have so much influence on new owners and directly influence the health outcomes of the puppies. I think that more pet companies need to appreciate the power of breeders.”

Breeding and breeders will continue to exist. That demand for 8.77 million puppies per year isn’t going anywhere—especially as adoption rates trail far behind buying rates in key markets like the UK, Germany and France.

Many puppies in shelters are victims of unethical breeders so the cycle perpetuates itself.

The International Organization for Animal Protection (OIPA) writes, “When authorities intercept illegal puppy transports, they typically seize the animals and transfer them to animal shelters. These shelters are then responsible for caring for the puppies, which often come with significant costs.”

The situation is dire, complex and requires a collaborative approach.

We can only hope that governments, ethical breeders, vets and pet tech startups can work together to carve a path forward for the betterment of our pets.

Written by Olivia De Santos, Pet Tech Writer @ Unleashed by Purina.

Special thanks to the breeders, veterinarians and industry experts who shared their insights for this article.

Unleashed by Purina in no way endorses the speakers in this article.